Month: October 2014

Rusty’s Retreat: A model to make red-tagged homes livable and benefit local nonprofits

Local trio sees Zayante rehab as a new model to legalize red-tags

by Jondi Gumz

Santa Cruz Sentinel

October 27, 2014, Felton — Rusty Hartman was a thorn in the side of the Santa Cruz County Planning Department but his dying wish, at age 75, was that his red-tagged retreat in the Zayante Hills would benefit children at risk. That was a tall order for his friend Wallace Wood, 75, trustee of Hartman’s estate, which owed money to contractors and was embroiled in legal disputes with former tenants.

Nonetheless, nine months after Wood asked a friend, real estate agent Lizabeth Morell, for help, and she called Michael Bethke, a contractor with 30 years of planning and construction experience, the trio is about to make Hartman’s impossible dream come true.

They will host an event 6-8 p.m. Thursday at the Santa Cruz Police Department community room to explain how red-tagged properties in the county could be rehabbed and legalized, making more housing available, providing jobs and generating income for local nonprofits.

“It’s definitely been a labor of love,” said Morell, an agent with Bailey Properties, enjoying the view of the fir trees and blue sky from sandstone deck with the tinkle of wind chimes above.

Hartman was an independent sort, doing most of the work at 9779 Rosebloom Ave. himself. “He was an amazing stone mason,” Wood said. He installed a rock path, built a gazebo and a water fountain. But he didn’t see the need to get county permits for improvements he made over 20 years, like enclosing a second floor deck to create more living space. The roof of the enclosed deck turned out to be too high by county regulations.

In terms of code violations, this was the worst Bethke had seen — “with a file yay thick,” he said, spreading his hands, and “82 trips to the dump” at the outset. Morell described Hartman as a hoarder, and as he got older, less capable of doing the work he wanted to do.

Bethke tapped Sid Slatter of Slatter Construction as general contractor while he navigated the permit process. The county called Hartman into court but the appearance came two months after he died and the judge ordered a $10,000 fine. Bethke tried in vain to get the fine waived. The county’s legalization assistance permit program, in the works for months, wasn’t effective until Oct.

Banks were skittish about making a loan. Morell said Jim Chubb of Pacific Inland Financial found a private investor from Monterey willing to take the risk. “Nobody in this county was interested,” Bethke said. The lender demanded 12 percent interest but tolerated complications, like paying that $10,000 fine along with the deferred property taxes and liens on the property.

Monday, two men from the Day Labor Center in Live Oak were working along with David Haltum, whose father Chris Haltum, is doing the hardwood floors. Sierra Azul is providing plants and San Lorenzo Rotary members have offered to help put them in.

Morell hopes the four-bedroom hillside home with jaw-dropping views on a acre of land will be worth “in the low-$700,000s.” That would cover the $350,000 loan with the remainder going to the Boys and Girls Clubs of the Valleys, 50 percent; Jacob’s Heart Children’s Cancer Services, 20 percent; antigang efforts PRIDE and BASTA, 20 percent; and the Resource Center for Nonviolence, 10 percent.

Morell welcomes donations of materials. “Any dollar we can save, we can send to the Boys and Girls Club or Jacob’s Heart,” said Bethke, who envisions his startup, dubbed For Sale For Good, becoming certified as a B corporation for benefitting the public good and turning more red-tagged problem homes into opportunities.

Rusty’s Retreat

What: An opportunity to learn about Rusty’s Retreat, a formerly red-tagged home at 9779 Rosebloom Ave. in the Zayante Hills that is being rehabbed for sale to raise money for nonprofits in Santa Cruz County serving children at risk; screening of “Rusty’s Redemption,” a film by Romney Dunbar.

When: 6-8 p.m. Thursday

Where: Santa Cruz Police Department Community Room, 155 Center St., Santa Cruz.

How to help: Call Lizabeth Morell, 831-688-7434, ext. 458, or email lmorell@baileyproperties.com

Here’s how many houses you can buy in other cities for the price of one in Silicon Valley

by Zainab Mudallal

Quartz.com

October 25, 2014, San Jose, CA — When the owner of a crumbling, uninhabitable house in a flood zone is asking for a cool $1.8 million, you know the market is hot. Amid signs that the national housing market is cooling, property prices in tech-heavy Silicon Valley show few signs of sanity.

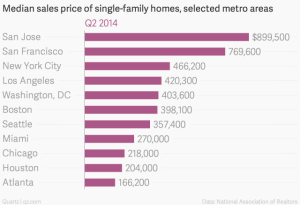

The median single-family home costs $900,000 in the San Jose metropolitan area, according to the latest figures from the National Association of Realtors. The area around San Jose, the biggest city in Silicon Valley, is closely followed by nearby San Francisco, with a median price that’s still more than $100,000 short of the typical home in the technology hub. And prices in both areas are rising by double-digit percentages, versus a low single-digit national average.

The median single-family home costs $900,000 in the San Jose metropolitan area, according to the latest figures from the National Association of Realtors. The area around San Jose, the biggest city in Silicon Valley, is closely followed by nearby San Francisco, with a median price that’s still more than $100,000 short of the typical home in the technology hub. And prices in both areas are rising by double-digit percentages, versus a low single-digit national average.

To fully appreciate how frothy Silicon Valley’s property market is, consider how many houses you can buy elsewhere for the same price as one in Apple, Google, and Facebook’s back yard.

Few people see the New York metro area as a particularly affordable place to buy a home, but your budget would just about fetch two houses in the Big Apple for the median price of one in San Jose. Or three in Portland, four in Philadelphia, and five in Orlando.

![]() Looking at these sorts of numbers, it’s no wonder that people are worrying about a potential property bubble, particularly at the high end of the market—homes over $1 million in San Jose have seen a 76% jump in price over the past year. But others think the boom has more room to run—newly minted tech millionaires can pay cash for their mansions, so there isn’t a particularly daunting debt overhang.

Looking at these sorts of numbers, it’s no wonder that people are worrying about a potential property bubble, particularly at the high end of the market—homes over $1 million in San Jose have seen a 76% jump in price over the past year. But others think the boom has more room to run—newly minted tech millionaires can pay cash for their mansions, so there isn’t a particularly daunting debt overhang.

But how long will the Valley’s budding captains of industry put up with just one place in San Jose when they could spend the same amount on an entire subdivision in an equally sprawling, featureless city somewhere else in the country?

———————-

Original article: http://qz.com/286239/heres-how-many-houses-you-can-buy-in-other-cities-for-the-price-of-one-in-silicon-valley/